Originally posted on www.courier-journal.com by Elizabeth Kramer, ekramer@courier-journal.com 6:38 p.m. EDT April 18, 2014.

Ron Karroll talks really fast. Is it because he’s from the East Coast, or is it because he’s excited about his new web-based business, Collabra?

The entrepreneur attributes his rapid-fire speech to growing up just north of Washington, D.C., but it’s obviously also fueled by new developments in his interactive music instruction venture.

“Like today, I got an email from a drummer who’s been playing for Elton John for 13 years. Being a drummer myself and having contact with these people is really cool,” said Karroll, 30, from his temporary office digs at Velocity, a business accelerator in Jeffersonville, Ind., that mentors start-up ventures.

This project, with Karroll as CEO and five other partners, is an online software application that allows people to record their music directly onto a program via a computer and mobile platforms in order to share it with others. Musicians can share with collaborators; students can share with teachers and parents. For the past several years, the partners have been seeking out musicians to look at and give them feedback on their project.

Next month, Collabra will get a boost when Mom’s School of Music becomes the first commercial music school to offer the program to its students. Owner Mark Maxwell and some of the teachers at Mom’s got to see the how Collabra works during a January presentation.

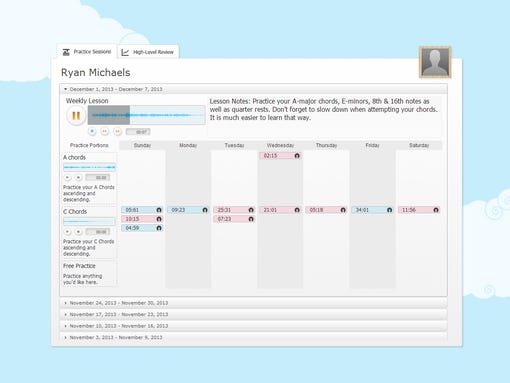

Student practice log(Photo: File photo)

Maxwell’s interest is important to Collabra, as Karroll and his partners see this partnership as a move that can lead to more students using it and make the company into a sustainable business.

Meanwhile, Karroll and others have been talking to colleges, high schools and elementary schools about including Collabra in their music education courses. He wants to see band and choral programs, as well as orchestras, using it.

Karroll and his team liken Collabra to Blackboard, the education software used by universities, K-12 schools and professional organizations worldwide. The difference is the music.

Instructors can record and archive lessons for their students to use, and students can do the same with their practice sessions for instructors, and even their parents, to review. The program also allows users to post notes at specific points in the sound clips.

Karroll came to create Collabra not as an entrepreneur looking for a venture but as guy in a band looking for a bass player. In 2010, Karroll, a drummer, was working at Humana with guitarist Ariel Caplan, and they had a band together.

“He asked if there was a website where we could find a bass player. I said, ‘Yeah, Craigslist,’ ” Karroll recalled of the question that got them talking about better ways the Internet could help find musicians they could collaborate with.

They envisioned being able to lay down tracks, guitar and drums for example, on a program where another musician, such as a bassist, could listen and then record a track for a screen that would show a multi-track recording. But they also wanted program users to be able to easily switch out tracks, say a bass line or guitar parts. That would allow users to easily test out different arrangements for music.

“We wanted it to be simple,” Karroll said. “We wanted people to be able to comment on our songs, and other people to be able to get on there and become their own producers.”

Alison Nelson, right, with music teacher Leora Nosko during a vocal lesson at Mom’s School of Music in Jeffersonville, Ind. Nosko joined the Collabra team as the program’s point person to assist other educators.(Photo: Frankie Steele/Special to the CJ)

“As we were talking about this to a lot of musicians, they were telling us that this would be great for their students who were too scared to start a band,” Karroll said.

That’s when the two began to shift the thrust of the business from musicians to music education.

As the idea developed, they brought on Humana colleague T.J. Mansfield, who had valuable IT skills developed in part at IBM. But in the past year, the initial team has brought in other partners, including Ryan Michaels, as a marketing director; Brandon Kobel, who came on board through an investor’s recommendation to handle adapting Collabra to mobile platforms; and music teacher Leora Nosko, who joined the team as the point person for educators. For now, only Karroll and Ryan, who joined last June, are working full time for the company.

By January 2013, Collabra had enough money to allow Karroll to quit his job at Humana to concentrate full time on cultivating the site and the company. So far, Collabra has earned financial backers outside of the partners.

One of them is Tim Sublett, a software expert who in 1998 started a company in Indianapolis called Aprimo, which developed marketing automation software. After selling Aprimo in 2011, Sublett went on to join a start-up called Zirmed before leaving to start another company that works with a metal 3-D printing process.

Sublett said Karroll’s passion for the project and his talent for writing code were deciding factors for him to get involved.

“That passion — you can see him as an artist creating code. That really resonated with me,” Sublett said. “He’s done some amazing stuff.”

While Sublett has been mentoring Karroll and his team for nearly a year, Collabra has other backers, including Greater Louisville Inc., the Kentucky Science and Technology Corp. and Southern Indiana’s Velocity. GLI sent Karroll to a Kauffman Foundation program for start-up companies.

It was through GLI that Sean O’Leary learned of Collabra. O’Leary has headed start-up companies and invested in them himself and is now with KSTC. After hearing Collabra’s pitch, he recommended that it receive a $30,000 grant over a year ago.

“What impressed us about these guys is that not only did they have a good idea, they had started to build something,” he said. “And while they were doing that, they were talking to potential customers and users. They kept refining as they were building.”

Although the Collabra team continues to court investors, it also is ramping up its work with educators. One of the key educators is Nosko, one of Mom’s 15 music instructors, who became a partner last fall.

She recalled getting a cold call from Karroll in which he began talking about Collabra.

“I was just about to blow him off,” said Nosko, adding that she didn’t when he proposed showing her the program in person. That’s when she “fell in love” with Collabra.

“It could do everything I had always wanted to be able to do with my students,” she said. “I require my students to record, and most use their iPhone and such. But it’s a big hassle. They run out of space on their phones, and I always wanted to trim parts of their lessons out, which I could never do.”

Nosko, who also had worked in marketing and advertising, began volunteering her time to Collabra and then was offered partnership.

Right now, Collabra seems poised to rise, but there are potential competitors out there, of which Karroll is well aware. Companies including Chromatik, Kompoz and SmartMusic in the United States and JamCloud in Sweden have all developed software designed to help people teach music and/or collaborate on music projects.

Christopher Woodside of the National Association for Music Education said that the organization is aware of some of the other programs but not Collabra.

“Some are really good. Some are really bad,” he said, declining to name any. “But this is a space that’s ripe with potential.”

But Karroll insisted that no one is doing what Collabra is doing.

“Collabra is simple and clear and makes education fun,” he said. “That’s a connection that hasn’t been made by any of the competitors yet.”

Karroll’s ambitions for Collabra run deep, but could Collabra or any similar program ever take the place of face-to-face lessons? For Maxwell, the answer is obvious.

“There’s no way it can,” he said. “Nothing can replace a human being showing you how to do something. Form is everything.”

Reporter Elizabeth Kramer can be reached at (502) 582-4682. Follow her on Twitter at @arts_bureau.